Introduction

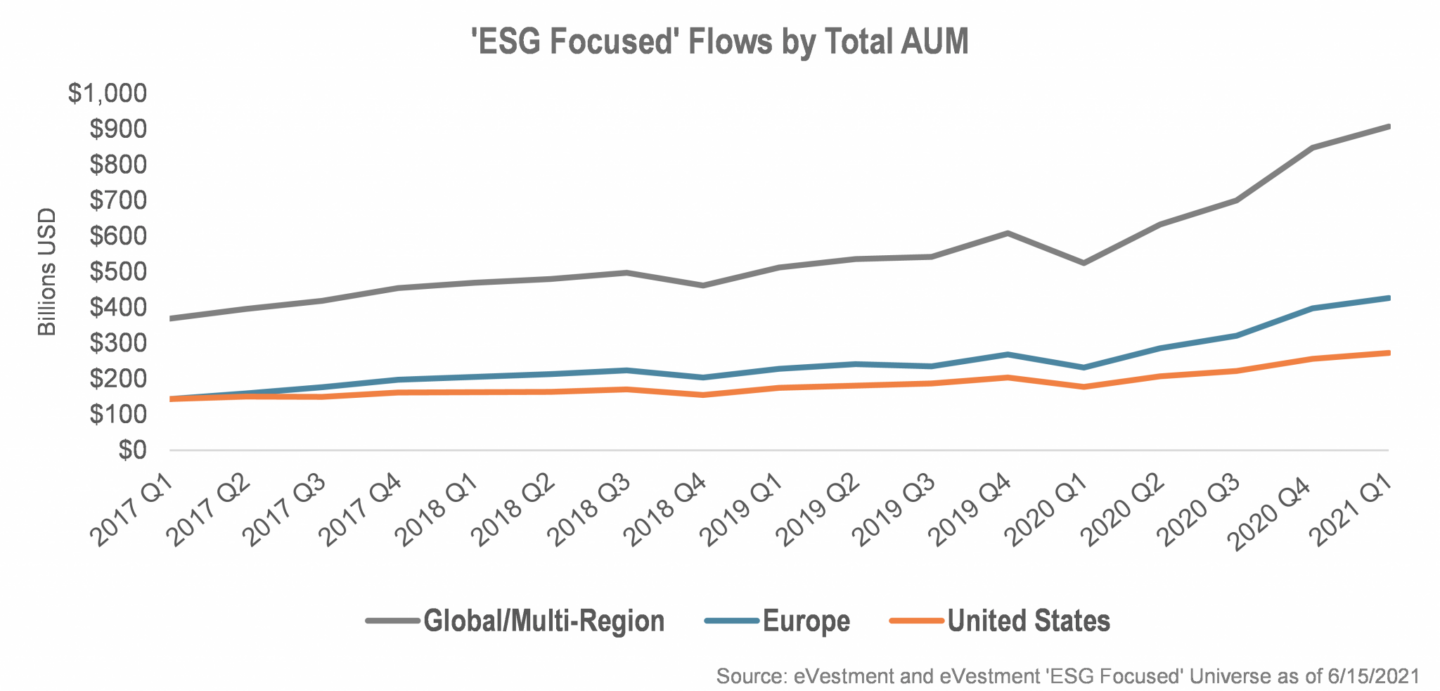

The rapid growth of sustainable investing in recent years marks an exciting time in the investment management industry and for investors seeking solutions beyond traditional investments.

However, the growing spectrum of sustainable investing capabilities has been blurred by an equally expanding sea of acronyms and terminology. SRI, ESG, RI, SDGs, Impact, Integration— many investment tools and terms have become conflated and misused, often leading to confusion for investors (See Appendix for an extensive list).

Sustainable Investing, sometimes known as Responsible Investing (RI), is the umbrella term encompassing this extensive assortment of acronyms. ‘Sustainability’ is an ambiguous term, often narrowly defined and fused with environmental sustainability. However, for investors, sustainability is typically defined as the aim to create long-term, sustained value for all stakeholders.

With no single metric or proxy to measure sustainability, investors have proactively turned to non-financial information, or ‘extra-financial’ information, in an attempt to capture sustainability. We define sustainable investing as considering these extra-financial factors alongside traditional financial metrics to determine the quality and risk of an asset. We believe evaluating these factors found outside typical financial statements can help capture additional risks and opportunities not otherwise found in traditional credit analysis.

There are many ways for investors to invest sustainably, and the industry continues to build out a spectrum of sustainable investment tools and strategies. This primer aims to provide our readers with a helpful overview of the sustainable investing space, including a brief history of sustainable investing, the growing array of sustainable investment approaches, and the latest innovations in the fixed income world.

History of Sustainable Investment

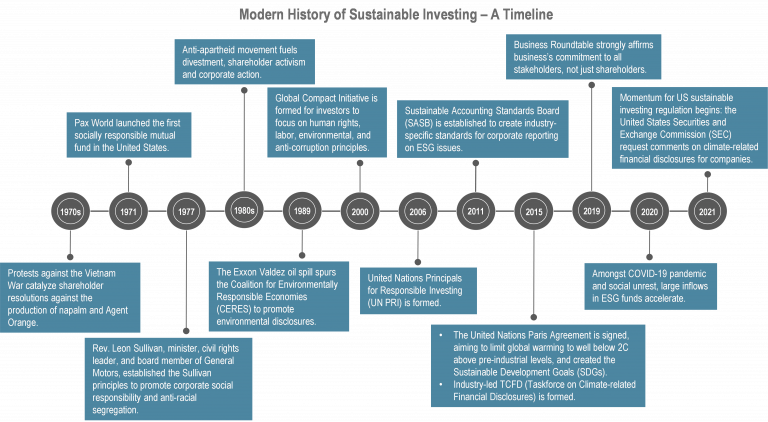

Sustainable investing has taken many forms throughout history. Consideration of extra-financial metrics originates from lending practices aligned with religious beliefs and values. Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) enables investors to do just that: express their personal values through their investment dollars, typically through the exclusion of certain names, industries, or sectors.

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI)

Socially responsible investing originates from restricted lending and investment activities based on religious practices and beliefs. SRI is still prevalent today, with exclusions for various “sin” industries (alcohol, tobacco, firearms, gambling, and adult entertainment), as well as specific activities such as the production of contraceptives, stem cell research, and use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Religious investment guidelines have since formalized for many faith-based investors; changing and nuanced investor preferences and market sentiments also influence the SRI space.

Modern social and environmental movements have spurred investor attention toward their portfolios with an SRI lens. For example, early 1980’s protests against the South African apartheid led to many investors divesting from companies doing business in South Africa. Investors’ preferences towards social and environmental issues have only become more sophisticated. Advanced screens exist for issues such as private prisons, coal reserves and/or revenue, and weapon production or defense-related spending. At IR+M, we have over 100 client portfolios with different SRI guidelines and continue to meet investors’ growing preferences and SRI needs.

Sustainable investing today encompasses SRI, but also presents broader solutions beyond moral or ethical goals. Additionally, the spectrum of sustainable investing can be pursued by the investor whose sole focus is financial performance.

‘Sustainability’ Defined: Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG)

SRI entails making binary judgements on whether or not to include a specific holding. How can investors make more concerted efforts to systematically incorporate extra-financial metrics and create relative judgements, similar to credit ratings?

ESG is an acronym that defines sustainability by categorizing extra-financial metrics under Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) pillars. Investing along the E, S and G pillars gives investors a useful lens of sustainable investing to inform holistic credit analysis.

ESG is now a ubiquitous lens to viewing sustainability. How does the ESG lens translate to effective investment research and incorporation? The sustainable investing space has grown to include many ESG data providers and third-party ESG reporting frameworks. However, there is a lack of consistency in the definition of E, S, and G and what underlying data points measure each pillar for a given entity. These definition and measurement issues result in noisy ESG data. On average, the correlation among prominent agencies’ ESG ratings was 0.61; by comparison, credit ratings from Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s are correlated at 0.92[1].

Central to these issues is the concept of materiality. ESG materiality demonstrates how ESG factors can be financially relevant to a specific issuer— in other words, how likely ESG metrics are to impact the long-term financial condition or operating performance of an issuer. Much of the inconsistency in how we define and measure Environmental, Social, and Governance pillars is due to the wide variance in how these factors apply to different issuers. Materiality varies across sectors or industries: the environmental risks applicable to a coal-mining company will look different for a technology firm. Overlaying these nuances is the question of data sourcing and availability— whether the data is from a primary source or estimated, and how recent or accurate data points are. These complexities ultimately make ESG metrics difficult to compare like credit ratings.

As the sustainable investment industry continues to develop, so will ESG materiality. What ESG factors investors believed to impact asset prices has dramatically changed over the years; as markets evolve and data collection progresses, our understanding of ESG materiality will further improve.

Industry-led groups such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) aim to help facilitate this transformation. Regulators globally continue to push for more effective ESG analysis and incorporation for investors. For example, the European Commission’s Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance (TEG) was formed to assist in developing legislation, including regulations on green taxonomy, green bond standards and mandatory climate-related disclosures for entities. This regulatory push has influenced US lawmakers, as well. The Sustainable Investment Policies Act was introduced in 2021, which would require investment advisors and retirement plan fiduciaries to establish a sustainable investing policy.

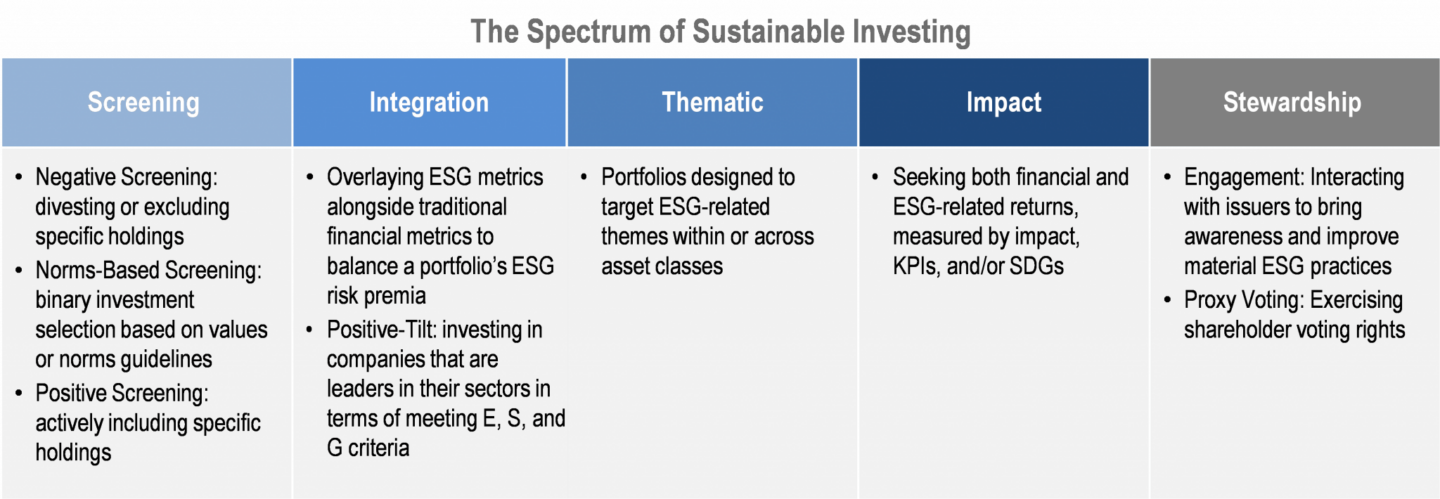

ESG Incorporation: The Spectrum

ESG is the lens investors use to create different sustainable investing styles and strategies. There are many ESG incorporation approaches that consider environmental, social and governance issues under the umbrella of sustainable investing.

The industry broadly classifies the various ways investors utilize ESG by their level of incorporation. Screening, Integration, Thematic, Impact and Stewardship are differing levels of ESG incorporation that create a true spectrum of sustainable investment approaches.

Screening

Screening is often associated with SRI, as it creates a binary decision between what holdings are included or excluded from a portfolio, dictated by preferences, values, or norms. Negative screening entails investors divesting or avoiding specific industries and holdings based on values or preferences. Investors can also positively screen and actively include specific holdings based on preferences, such as environmental and social norms.

Integration

Integration takes this binary approach one step further. Instead of deeming a holding acceptable or not, investors determine a categorical ‘goodness’ of a specific holding relative to others and weight accordingly. ESG integration can be seen as an extension of holistic credit analysis — valuation, not values.

ESG integration can be further differentiated by how much investors weigh or prioritize ESG performance for a given holding. Overlaying ESG metrics alongside traditional financial metrics recognizes and attempts to balance a portfolio’s ESG risk premia by holding assets with varying ESG performance. Positive-tilt strategies explicitly favor higher-performing ESG holdings in order to steer investment capital toward ESG leaders within a given industry.

Thematic

ESG can also be leveraged to create more sophisticated, focused sustainable investing strategies. Thematic strategies may cater to clients’ desires for both financial returns and a specific E, S, or G focus or theme. Themes can include broader ESG-related concepts such as healthcare, inclusion and diversity, or renewable energy. Thematic funds may also capture sub-sectors and related trends such as affordable housing, automation and robotics, or circular economies.

Impact

Thematic strategies are close relatives with impact investing. Impact investing strategies are differentiated by their rigor of reporting as they seek both quantifiable financial and E, S or G-related returns. ESG or impact returns can be measured by Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)— specific and measurable outcomes such as reduction in carbon emissions or increase in low-income housing units developed.

Impact outcomes, as well as thematic strategies, are also commonly aligned with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which outlines 17 goals for sustainable development designed to reduce inequality and care for the environment. However, given the general lack of reporting standards for impact outcomes, it is often difficult to compare non-financial returns across strategies.

Stewardship

Investment stewardship, also known as active ownership, generally refers to the responsible management of clients’ investments as active owners. Stewardship complements ESG incorporation strategies by engaging with company management or deal sponsors to better understand and evaluate their ESG performance and longer-term sustainability. The goal of stewardship can also go beyond comprehensive research and aim to influence how ESG issues are managed. Active ownership can help promote issuer transparency, data alignment with industry standards, and ESG best practices.

As demonstrated by SRI and negative screening strategies, investors also have the power to influence by simply divesting. The Divest vs. Engage debate continues to be nuanced as environmental, social and governance issues can be equally complex. For example, there are inarguable benefits to reducing the world’s dependence on fossil fuels. However, the path to doing so is complex. Divestment would assume that the capital outflows have a large enough impact to change companies’ strategies, and engagement assumes support for strategic transition will bear material in the future. In many cases, divestment can morph into engagement over time. Ultimately, accommodating for clients’ own divestment and engagement approaches may drive both ESG incorporation and stakeholder value.

Innovations in Fixed Income Sustainable Investing

Sustainable equities strategies have led the charge in the swift growth of sustainable investing in recent years. Identifying additional risks and opportunities with an ESG lens is equally important for fixed income investors, yet the asset class has historically lagged in advancing sustainable investment capabilities.

Fixed income investors face unique challenges in incorporating ESG within their portfolios, such as finite duration, maturity, and differing term and call structures. Investors also work with a larger investment universe, with varying instruments spanning corporate bonds, securitized debt, sovereigns, and municipal bonds. The ESG industry, particularly ESG data providers, often lack the reporting and data coverage needed for fixed income ESG analysis as well. The complexities inherent in fixed income investing and lower data transparency make it more difficult for these investors to efficiently identify ESG-related risks and opportunities.

Nonetheless, fixed income investors are essential to fully bridging traditional and sustainable investing in the industry. A leading trend pushing fixed income sustainable investing is the issuance and growth of ESG-labeled bonds.

ESG-Labeled Bonds

As part of the growing effort to incorporate ESG in fixed income securities, ESG-labeled bonds present an attractive solution for investors seeking direct sustainable investments.

Also known as Green, Social, Sustainability (GSS) and Sustainability-Linked Bonds, ESG-labeled bonds are a means of raising finances for projects with E and/or S benefits. Green bonds designate a specific use of proceeds towards projects that promote climate, conservation and/or biodiversity objectives, for example renewable energy or green building projects. Social bonds are issued so that use of proceeds address a social issue or need, such as marginalized groups’ access to healthcare. Sustainability bonds specify the use of proceeds for an intentional mix of environmental and social projects. A close variant, Sustainability-Linked bonds are also issued for general corporate funding but link issuers’ KPIs to environmental objectives or the SDGs— use of proceeds for a specific project are not specified.

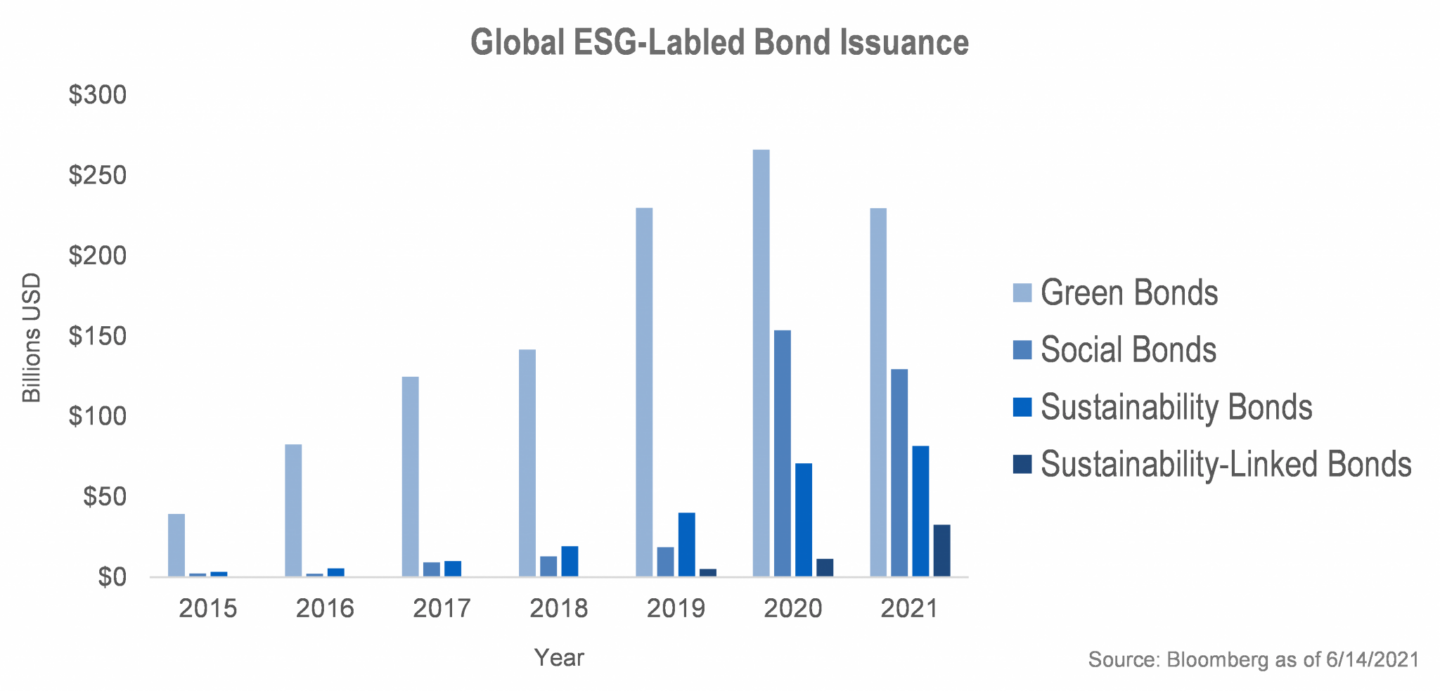

Industry guidelines and voluntary standards, such as International Capital Markets Association (ICMA), recommend that issuers of ESG-labeled bonds enlist third party auditors to externally verify and subsequently report on the use of proceeds or KPI performance. Demand for ESG-labeled bonds has increased accordingly, especially for social and sustainability-linked bonds with 2019-2020 year-over-year growth over 700% and 100%, respectively.

While ESG-labeled bonds have driven growth in fixed income sustainable investing, external verification and certification are widely debated for its efficacy. Many investors and practitioners argue that external verification often provides perverse incentives for weak authentication and ‘greenwash’— overstating the project’s sustainability merits or KPIs. Tracking the specific uses of proceeds and KPIs for these labeled bonds also creates complex accounting issues and increased costs. In low interest rate environments, some issuers may be disincentivized to bring ESG-labeled bonds to market due to these complexities.

Sustainable Investment at IR+M

We believe that viewing our investments through an ESG lens is an integral part of risk assessment when evaluating securities. Incorporating ESG factors allows us to mitigate downside risk and identify investment opportunities influencing long-term sustainability and creditworthiness.

As an active investment manager, ESG is fully embedded in our investment process. Our research analysts are sector specialists who determine and analyze material ESG factors across subsectors to identify risks and opportunities that may impact long-term performance. This integrated approach ensures that all analysis considers material ESG factors alongside traditional financial metrics, providing a more holistic view. During the portfolio construction process, our portfolio managers account for material ESG issues alongside relative value, liquidity, and other material investment factors. We cater to our clients seeking solutions across the spectrum of ESG incorporation, with specified ESG strategies spanning SRI, screening and positive-tilt portfolio solutions.

Across our strategies, we utilize our proprietary ESG Key Issues Map to analyze material ESG factors throughout all sectors. Our Key Issues Map identifies 35 key issues, such as climate change, labor relations, compliance, across the E, S, and G pillars. Our ESG research process is complemented by our engagement efforts with issuers. We believe that issuer engagement is crucial to understanding and evaluating the longer-term sustainability of our holdings; it also presents an opportunity to encourage ESG best practices that can drive material, long-term value. This holistic, embedded ESG approach leads to a more complete understanding of potential material issues, which we believe will ultimately result in superior risk-adjusted returns over the long-term.

IR+M has been a signatory to the Principles for Responsible Investment (“PRI”) since 2013, which marked an important milestone in our own history of sustainable investing. Our sustainable investment capabilities continue to expand to meet the needs of clients and advance ESG incorporation in the fixed income space.

Conclusion

This primer aimed to provide our readers with an overview of sustainable investing, including the history of sustainable investing, evolution of ESG, the spectrum of sustainable investing capabilities and innovations in fixed income.

The modern history of sustainable investing originates from SRI, which continues to evolve today as more investors seek to align their preferences with their investment dollars. The rise of using ESG as a lens to define sustainability has helped investors identify ‘extra-financial’ risks and opportunities in investments. Still, there are significant opportunities for the sustainable investing industry to improve. Inconsistencies in ESG data and reporting highlights the current hurdles to standardize ESG materiality across entities. Despite the challenges, the ever-growing spectrum of sustainable investing capabilities continues to give investors greater options for ESG incorporation, whether it be through screening, integration, thematic or impact strategies.

Issuance of ESG-labeled bonds has also grown to meet increasing client demand for fixed income sustainable investment solutions. While advancing ESG capabilities within this asset class faces unique obstacles, IR+M continues to expand our sustainable investment capabilities to meet the needs of clients and advance ESG incorporation in the fixed income space.

Appendix

Key Terms

Sustainability: the aim to create long-term, sustained value for all stakeholders.

‘Extra-Financial’ Information: data inputs found outside typical financial statements that can help capture additional risks and opportunities not otherwise found in traditional credit analysis.

Sustainable Investing: considering extra financial (ESG) metrics alongside traditional financial metrics that together speak to the quality and risk of an asset.

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI): enables investors to express their personal values through their investment dollars, typically through the exclusion of certain names, industries, or sectors.

Negative Screening: divesting or excluding specific holdings because of investor preferences or values.

Positive Screening: actively including specific holdings.

Norms-Based Screening: binary investment selection based on values or norms guidelines.

ESG: acronym that defines ‘sustainability’ for investors by categorizing extra-financial metrics under Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) pillars.

Materiality: how likely ESG factors can be financially relevant to a specific issuer, i.e., impact the long-term financial condition or operating performance of an issuer.

ESG Incorporation Spectrum: broad industry classification of the various ways investors utilize ESG in investment strategies by their level of incorporation.

ESG Integration: overlaying ESG metrics alongside traditional financial metrics to balance a portfolio’s ESG risk premia by holding assets with varying ESG performance.

ESG Positive-Tilt: explicitly favor higher-performing ESG holdings in order to steer investment capital toward ESG leaders within a given industry.

Thematic Investing: caters to clients’ desires for both financial returns and a specific E, S, or G focus or theme; examples include healthcare, inclusion and diversity or sustainable energy, automation and robotics.

Impact Investing: investment strategies that seek both quantifiable financial and E, S or G-related returns.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): set of specific, quantifiable outcomes impact strategies aim to achieve with respect to the Environmental, Social Governance pillars or SDGs.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): outlines 17 goals for sustainable development designed to improve sustainable global growth, reduce inequality, and care for the environment; often guides thematic strategies and impact investing KPIs.

Investment Stewardship (Active Ownership): responsible management of clients’ investments as active shareholder and/or bondholders; includes proxy voting and engagement.

ESG-Labeled Bonds: raises finances for projects with environmental and/or social benefits; encompasses Green, Social, Sustainability (GSS) Bonds.

Green Bonds: designated specific use of proceeds towards projects that promote climate and/or environmental projects.

Social Bonds: instruments whereby use of proceeds address a specific social issue or need.

Sustainability Bonds: specified use of proceeds for an intentional mix of environmental and social projects.

Sustainability-Linked Bonds: issued for general corporate funding but link issuers’ KPIs to environmental objectives or the SDGs— use of proceeds for a specific project are not specified.

International Capital Markets Association (ICMA): self-regulatory organization facilitating the leading frameworks for The Green Bond Principles (GBP), The Social Bond Principles (SBP), The Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBG) and The Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles (SLBP).

UN PRI: Principles for Responsible Investment is a United Nations-supported international network of investors aimed to promote sustainable investing and ESG incorporation.